Tutto Ponti : Gio Ponti Archi-Designer

Exhibition review

Disegno #21

March 2019

The Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris has rebranded itself as MAD Paris. MAD is no longer simply an acronym of its former name but instead of “‘mode’ (fashion), art and design”. Opening its autumn exhibition season is a show dedicated to the work of the Italian architect and industrial designer Gio Ponti (1891-1979). It is Ponti’s first retrospective in France and it seems an obvious choice for the museum to highlight a figure whose career helped shape design in the 20th century at this point in its existence.

In parallel to the exhibition, the museum has also unveiled a reorganisation of its modern and contemporary holdings entitled La folle histoire du design, or The Crazy History of Design. This proposes a new global vision of the museum’s collection that particularly highlights transdisciplinary practices. Since the beginning of 2018 the museum – located in a 19th-century wing of the Louvre – has tried to shake its reputation of being dedicated solely to decorative arts by also highlighting the contemporary relevance of its collections. With _Tutto Ponti: Gio Ponti Archi-Designer and La folle histoire du design, an eclectic image of design emerges.

The influence of Gio Ponti is omnipresent in the fields of architecture and design. Tutto Ponti offers a chronological journey through the “archi-designer’s” career. Francesco Pastore, assistant curator of the exhibition, says that in selecting its title they had hoped to convey Ponti’s multifaceted oeuvre in a somewhat humorous fashion. Before the 1980s, there was no discrete design pedagogy in Italy and most industrial designers active in the postwar years were formally trained as architects before developing an object-based practice. Today, a vocabulary that grasps the idea of a fluid, transdisciplinary way of working still remains to be developed. In an homage to Ponti written in 1985, Alessandro Mendini lists 30 terms describing Ponti’s career, beginning with “painter”. It isn’t until sixth and seventh on the list that Mendini arrives at “designer” and “architect”. Even Ponti added to the ambiguous nature of his practice when he stated, “I am an artist who fell in love with architecture” – a quote deemed important enough to be displayed prominently as a wall text in the exhibition.

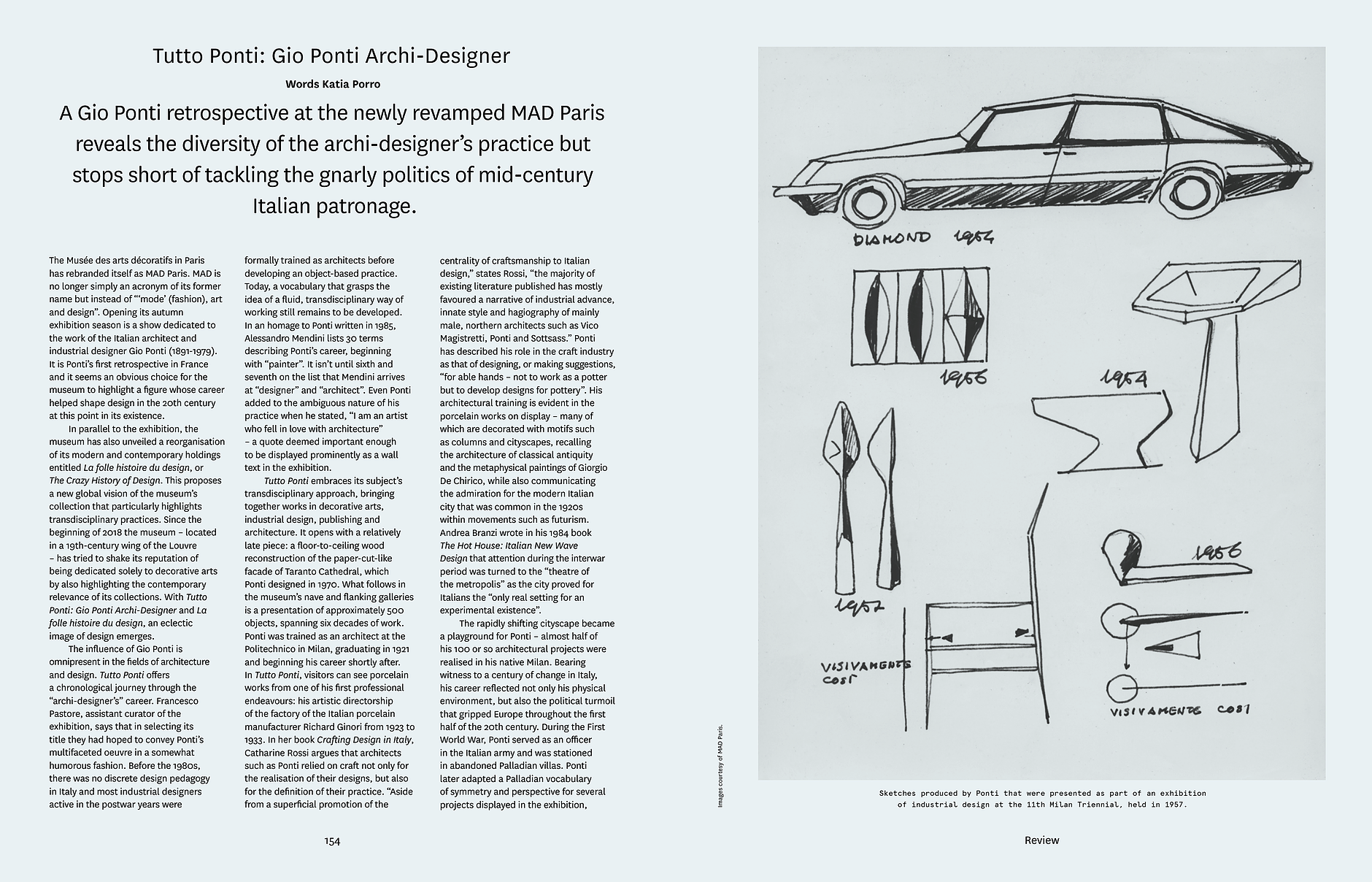

Tutto Ponti embraces its subject’s transdisciplinary approach, bringing together works in decorative arts, industrial design, publishing and architecture. It opens with a relatively late piece: a floor-to-ceiling wood reconstruction of the paper-cut-like facade of Taranto Cathedral, which Ponti designed in 1970. What follows in the museum’s nave and flanking galleries is a presentation of approximately 500 objects, spanning six decades of work. Ponti was trained as an architect at the Politechnico in Milan, graduating in 1921 and beginning his career shortly after. In Tutto Ponti, visitors can see porcelain works from one of his first professional endeavours: his artistic directorship of the factory of the Italian porcelain manufacturer Richard Ginori from 1923 to 1933. In her book Crafting Design in Italy, Catharine Rossi argues that architects such as Ponti relied on craft not only for the realisation of their designs, but also for the definition of their practice. “Aside from a superficial promotion of the centrality of craftsmanship to Italian design,” states Rossi, “the majority of existing literature published has mostly favoured a narrative of industrial advance, innate style and hagiography of mainly male, northern architects such as Vico Magistretti, Ponti and Sottsass.” Ponti has described his role in the craft industry as that of designing, or making suggestions, “for able hands – not to work as a potter but to develop designs for pottery”. His architectural training is evident in the porcelain works on display – many of which are decorated with motifs such as columns and cityscapes, recalling the architecture of classical antiquity and the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio De Chirico, while also communicating the admiration for the modern Italian city that was common in the 1920s within movements such as futurism. Andrea Branzi wrote in his 1984 book The Hot House: Italian New Wave Design that attention during the interwar period was turned to the “theatre of the metropolis” as the city proved for Italians the “only real setting for an experimental existence”.

The rapidly shifting cityscape became a playground for Ponti – almost half of his 100 or so architectural projects were realised in his native Milan. Bearing witness to a century of change in Italy, his career reflected not only his physical environment, but also the political turmoil that gripped Europe throughout the first half of the 20th century. During the First World War, Ponti served as an officer in the Italian army and was stationed in abandoned Palladian villas. Ponti later adapted a Palladian vocabulary of symmetry and perspective for several projects displayed in the exhibition, notably in the furniture he designed between 1924 and 1926 for his family apartment in via Randaccio, Milan, and the country house, l’Ange volant, which he designed for Tony Bouilhet in 1928. One of the six period rooms in the exhibition recreates the entrance hall of l’Ange volant, located in the Parisian suburb of Garches. The facade represents a marriage of modernism and tradition: a nearly undecorated exterior penetrated with systematically placed windows, two of which bear broken pediments, and a classical Italian portico. This embrace of modernism veiled by an affection for tradition exemplifies the uniting of the past and the present often found in Italian architectural practices throughout the 20th century. In his 1957 text Amate l’Architettura (or In Praise of Architecture), Ponti stated: “All art, present and past, is simultaneous in our culture. We must understand that we are contemporaries also of Raphael because he is contemporary with us in our culture[…] We must measure ourselves with the past but also with the future.”

This reverence for the past as informant of the future, and Ponti’s extensive research into international architecture and design cultures synthesised when he founded the influential architecture magazine Domus in 1928. The magazine, which celebrated its 45th anniversary at Paris’s Musée des arts décoratifs in 1973, is highlighted in Tutto Ponti, and can be considered one of Ponti’s masterpieces. It served as a platform to explore all forms of creative expression, introducing its Italian readership to international design. Domus, in which Ponti published hundreds of articles and featured works and texts by other designers, Italian and foreign, quickly became a meeting place for international ideas as well as a vehicle for the promotion of modern design. By the end of Ponti’s career, the publication had developed into a multilingual magazine with a global readership. His editorial endeavours were not exclusively linked to Domus, as he also founded the magazine Lo Stile, and collaborated with others such as Aria d’Italia, Bellezza and the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. Editorial activities have proven to complement several designers’ practices, particularly in Italy, with examples including Alessandro Mendini (a successor of Ponti at Domus as well as editor-in-chief of magazines Modo and Casabella) and Ettore Sottsass (cofounder and editor of East 128, Pianeta Fresco and Terrazzo; and contributor to Casabella and Domus). Today, it is crucial to regard design practice as something fluid, with explorations in publishing capable of nourishing production. With Domus, Ponti not only proposed his ideas of total design and the art of living but also shed light on how design practices are intrinsically transdisciplinary.

What is little-mentioned in Tutto Ponti, however, is the polemic that lies at the heart of the Italian modernist movement. During the fascist regime, Italy underwent a period of transformation in which many celebrated architects played a major role. Architecture and design history has often disregarded the controversial conditions under which some of its most celebrated creators established their careers – ultimately allowing for a purely aestheticised presentation of the period. As Branzi puts it, design is “prey” to historical amnesia. It’s complicated to address this context in a museum retrospective, but the function and patronage ought not be removed from objects or buildings. Ponti’s most notable constructions of the period were the Department of Mathematics for the University La Sapienza of Rome (1932-1935) and the office buildings for the chemical group Montecatini (1935-1938) – the former commissioned by Mussolini himself, the latter by one of his supporters, Guido Donegani. Donegani was known to have fully accepted the dictatorship and it was under his direction that Montecatini began producing the synthetic nitrogen that proved essential to Mussolini’s goals: ruralism, militarism and autarchy. In Tutto Ponti, a reconstruction of the Montecatini offices is featured with a wall text simply stating that the “Montecatini [group’s] interests included the chemical, metallurgical and electrical industries, perfectly [illustrating] the tremendous economic development occurring in Milan in the 1930s.” There is no mention of how Montecatini’s visions were guided by the ideals of fascism.

Another project worth mentioning, albeit realised after the fall of the fascist regime in the 1940s, is the celebrated Pirelli tower in Milan. For this project, Ponti was commissioned by Alberto Pirelli, the principal economic adviser to Mussolini. Although Ponti has been considered politically moderate in that he was not an active member of the party – as compared to architects who openly subscribed to fascist ideals, such as the Gruppo 7 – he nonetheless contributed to several of Mussolini and his followers’ visions. Architectural historian Diane Yvonne Ghirardo has written about the architecture of the Italian modern movement, describing it “as modern as it is fascist”. This is worth consideration in relation to Tutto Ponti. Design is intrinsically political and the ignorance of the contentious conditions under which commissions have been made seems archaic today.

The Second World War put an end to the fascist regime and called for a rigorous rebuilding of Italy, requiring significant efforts from architects and designers. The economic boom precipitated by the Marshall Plan and the reopening of borders in the 1950s and 1960s allowed for Ponti’s continued success in Italy and abroad. With international commissions from Venezuela to the United States, he took on a leading role in a globalising world of design. Postwar Europe not only witnessed a wave of reconstruction, but also the rise of mass production as a result of new consumer capital. This dolce vita period gave birth to one of Ponti’s masterpieces, the Superleggera (or super-light) chair produced by Cassina in 1957. Ponti sought to refine massproduced objects and the Superleggera was born after a decade of research and tests by him and the craftspeople employed by Cassina. Directly inspired by a vernacular chair used by fishermen in the Ligurian coastal village Chiavari, the chair transformed into a finished product weighing just 1.7kg. It not only reflects Ponti’s search for lightness but also the complicated system of subcontracted labour that arose in Italy during this time. The frame was realised by the firm’s head carpenter, Fausto Redaelli, and the handwoven seat was made in Chiavari by impagliatrici (female straw weavers), giving insight into the reliance on artisanal skills during a moment of industrialisation. As Rossi explains, “design and craft co-existed in a deeply inter-woven and complex relationship, and the production, dissemination and consumption of the former was continually and actively shaped by the presence of the latter, be it through its embrace or negation.” This complicated relationship between craft and industrial design holds true not only in the case of the Superleggera, but also a majority of Italian postwar design.

As with any retrospective of such a prominent historical figure, we must consider why Ponti has been regarded as revolutionary and what we can learn from him today. Architecture and design practices require a thorough understanding of the complex world and the various facets that make up the built environment, or as Ponti stated, “Architecture is the concrete result of human activities that it both interprets and expresses.” From the period rooms to the handwritten letters Ponti sent his friends and family, and from the everyday objects such as spoons and espresso machines to his contributions to theatre, Tutto Ponti bears witness to its subject’s advocacy for a synthesis of the arts. Influenced by schools such as the Wiener Werkstätte and Bauhaus, each of Ponti’s creations were part of a larger, total design project. Through the hundreds of articles Ponti published, as well as his manifesto Amate l’Architettura, Ponti provided the design world with visions of how different practices can inform each other, and how the past can influence the present and future, thereby establishing foundations for design in the 20th century. In contemporary practice, this idea of a practitioner working across disciplines proves more complex than it was for designers in Ponti’s time, who relied heavily upon commissions by the state or wealthy patronage. The advances in design education and various specialised programmes have also compartmentalised specific skills. However, what can be absorbed is the idea of a synthesis and an understanding that strong work draws on diffuse fields. Design permeates the world around us and contemporary practices should continue to embrace its transdisciplinary nature.

Perhaps more importantly, Tutto Ponti gives rise to the question of how and by whom design histories are written and told. Two of the four curators of the exhibition are directly related to Ponti: Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas, his great-niece, and Salvatore Licitra, his grandson. This provides an answer, perhaps, as to why the controversial foundation of Italian modern design is hardly mentioned, neither in the exhibition nor in the catalogue. In a moment of international uncertainty, however, it seems crucial to acknowledge the conditions under which many pioneers of modern design established their careers. Ponti was symptomatic of his time and his work cannot be extricated from its context. In order to render such figures relevant today, we must observe every aspect of their careers, particularly in moments of political tension. This is not simply a call to scrutinise Ponti’s commissions in the 1930s, but rather to observe how he was able to reinvent himself after this period and thereby help to establish roots for Italian design’s development over the course of the second half of the 20th century. Architecture and design call for constant transformation; with Tutto Ponti we are offered a vision of how a designer restlessly transformed over the span of 60 years.